Introduction to Rene Ricard 1979-1980

Rachel Valinsky

In 1980, the Dia Art Foundation, founded six years prior by Philippa de Menil, Heiner Friedrich, and Helen Winkler, published its first volume of poetry. The “poetry series” saw its rise and fall with Rene Ricard’s provocative collection, Rene Ricard, 1979–1980. The book—this book—is a testament to that moment of intersection between a young arts institution and the flaming poems of a young Rene, making his way through the social, literary, and art worlds of New York. The singularity of his voice—the voice of a vigorous and vulnerable author, writing with raw energy of his lovers, enemies, and desire for revenge, of his fatigue of the rich, his sorrows, his social woes, and his absolute presence of being—resounds forcefully today still.

The story is often recounted that Rene left a more than troubled family upbringing and a sexually and socially exhausted Boston behind to make his way to the doorstep of Andy Warhol’s Factory in New York. The press release disseminated when the book was published repeats this narrative, emphasizing the precarity of these poems and their emergence in the world: “It is very easy to think that Rene Ricard might have been lost to us, that the depths of an amphetamine culture or the heights of pop art society might have all missed him had he not thrown himself forward in our time—in 1965 to be exact—a young, very lean, very shy teenager who hitchhiked from Boston to New York wanting to meet with all the beautiful people he had read about in the newspapers and art magazines.”

He developed a close friendship with the poet, editor, photographer, and Warhol Screen Test collaborator Gerard Malanga, who would ultimately be engaged by the Dia Foundation to steward the editorial process of Rene’s publication. This process, as a conversation with Malanga, and research in his papers at the Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Yale University reveal, would prove trying, even painstaking at times. Rene’s famously itinerant and lively social life (he often stayed at friends’ houses, while later in his life, his Chelsea Hotel room largely served as storage) incurred delays in editing and design at key stages. He tended to scatter and lose poems, for instance, making Malanga’s work of collecting, safeguarding, and editing them essential (in this task, over the years, he has not been alone). Rene was uncompromising on the book’s design. Recall that iconic Tiffany blue cover, perfectly analogous to the jeweler’s catalogue, down to the lamination: “Any departure from the Tiffany catalogue prototype would be a liability” instructs Malanga to the designer, Bruce Chandler, in a letter dated March 27, 1979. Rene was unreachable when needed. Writes Malanga, in an urgent February 17, 1979 letter to the author: “Rene: This is a last-ditch effort by Eileen [Bresnahan, a friend] and myself to connect with you somehow to give you the last galley-sheets to your mss… Since I am the one with a phone it is your responsibility to put yourself in touch with me… WHERE ARE YOU!!!!?”

It would be easy to write off the history of Dia’s short-lived publishing series, attributing its brevity and singular output to the difficulties of working with its first, exacting but elusive author. In a number of thoughtful proposals, Malanga had charted the program that would follow: a reading series, a steady output of publications, with three or four volumes released each year. Victor Khlebnikov, Paul Blackburn, John Wieners, and Angus MacLise, among others, would have followed Rene, on Malanga’s unrealized imprint, Logos. Yet Rene’s book was already positioned, or more aptly, already positioned itself, within an altogether different register. In a manifesto-like letter to Heiner Friedrich dated February 17, 1978—shortly after Friedrich picked up the book from Ted Berrigan’s C Press, which couldn’t fund the project—Rene situated his work in relation to those better funded arts projects occupying Dia’s attention (and budget):

“The Dia Foundation seems to have tremendous amounts of money. It probably doesn’t seem like all that much to Dia, but let me draw your attention to the fact that one Walter De Maria lightning rod costs more than I’ve ever earned. LaMonte Young’s piano ditto. I am no way trying to diminish the importance of these men’s work, merely trying to point out that my poems carry as much artistic weight. It just seems unfair to me in light of how much Dia spent on its John Chamberlains that it would try to get Rene Ricards for five hundred dollars down and fifty percent of all royalties for the next five years. This manuscript of ninety pages has taken me twelve years to assemble.”

And he continues: “The poems themselves must not be confused with the book that contains them; I am not a writer. I make poems. They could be on graven tablets, cast in bronze (not a bad idea), or blown-up wall-size (which I’ve done and they’re great looking). No, a book is merely the most portable and convenient way of getting them to the general public the way a reproduction of a picture is the most inexpensive way of distributing the information the picture contains. It must be born in mind that there is no ‘original’ for the poet to sell. The poet himself is the original. He has no distance from his work, can’t step back and enjoy the effect like a painter because he is constantly geared for work, and in a literal sense his life is his art.”

For Rene, the poem’s material support takes the form of a book almost incidentally, spurred by that medium’s convenient dissemination and low production cost. His reclamation of the value of his work (as strategic as it may be) and his reformulation of his position as an artist, or a crafter of poems, constitutes a significant statement of intent. For in this letter, emerges not only a poetics but also a call for compensation for labor which he deems indissociable from the life of the artist. Negotiating the terms of an economy in which a poet could never claim, even level-headedly, the same fee or financial reward as an artist producing monumental land art, or soon-to-be blue-chip art, or have his writing in book form circulate as a high-priced luxury art commodity, Rene clearly re-articulated the locus of his work in himself, and for this, he donned the artist’s dress.

Rene had written something to this effect, though far more polemically perhaps, in his New York Times Op Ed, dated November 20, 1978, “I Class Up a Joint.” There he exclaims, proudly, “I’ve never worked a day in my life,” and continues, “The fact of the matter is that if I worked a straight job I wouldn’t have time to do the serious business of my life, which is to amuse and delight, giving my rich friends a feeling of largesse, my poor friends a sense of high life and myself a true sense of accomplishment for having become a fixture and a rarity in this shark-infested metropolis.” The reader of these nearly contemporaneous claims might approach this collection of poems hoping to glimpse the life of a socialite, a court jester. And certainly these roles, slipped into ever so easily, at times shimmer throughout these poems. But more often than not, that evocation of glamour turns sour—or rather, is stripped bare of its allure—in the poem. Writes Rene in “On Being Called a Dilettante”:

There is no cushioning layer of beauty

Between the harsh realities of life.

And he continues:

Brice Marden called me a dilettante

The other night. It serves me right.

I don’t make a big deal about my talent

And am so unsure about the quality of

My work that I never show it to people

So I guess they think I don’t do anything.

I’ve never earned a penny from my work

Which does in a sense make it worthless.

Though always tinted with some irony, these poems emphatically demonstrate the “literal sense” in which the poet’s “life is his art,” a claim which reverberates throughout the book. The life of the poet is, of course, often the greatest source from which to draw in writing. But these poems do more than merely document the friends and enemies, places, and feelings of Rene’s daily life. They turn sculptures to life in ekphrastic delight. They negotiate the line between privacy and publicness, at each turn working through a public address and private form of feeling and note-taking. They call out for a reader while turning in on themselves in solitude; they decry failed romances whose most intimate details Rene propels into public knowledge while also unveiling the personal echoes of heartbreak experienced, as they manifest in nostalgia, sordid fantasy of revenge (“I was born” may be one of the most virulent revenge poems ever written), and deep-seated grief. They linger in the after-hours of revelry, when once ecstatic relations have faded only to emerge again in memory, shadows of themselves. Consider this excerpt from the poem that begins: “Love: I did the homework but flunked”:

Things are no longer deeply felt

as I ascend the grand staircase

of indifference. Discarded party favors

lay on the floor below.

they were my feelings.

I have a headache.

all these feelings like the remains

of an orgy in the morning light

cigarettes in half-empty glasses

In 1980, it might have been possible, in the press release for this book, to write, “Rene Ricard’s poems come from nowhere; they are neither causative nor certainly with any history.” Today, it is in part for the way they have indelibly left their mark on the history, people, and literary and art worlds of New York and beyond that Rene’s work should be re-read. They continue to compellingly approach today’s reader in their immediacy, their determination to say all without compromise or reserve, in the risks they take in exposing the vulnerable, precarious, but also licentious self. The world his poems evince and draw out generously offered itself up for translation, and in this way, gave us the opportunity to linger with Rene Ricard for three years to produce his first French translation, published here in a bilingual volume.

Rachel Valinsky

New York, 2018

-

Rene Ricard was an American poet, artist and actor. He was born in 1946 and grew up in New Bedford, Massachusetts. After a troubled childhood, he fled to Boston as a teenager where he came into contact with literary and artistic circles. At the age of eighteen, he moved to New York City and became a central figure in the city’s art and literary scene. Ricard appeared in several films by Andy Warhol and continued to act in many independent films throughout his life. In the 1980s, he wrote two major collections of poetry, as well as important essays and articles, some of which were instrumental in launching the careers of artists such as Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat (he wrote the famous article “The Radiant Child” in Artforum in 1981). Beginning in the 1990s, he developed a pictorial body of work and exhibited his paintings in various galleries in the U.K. and the U.S. He died in New York in 2014.

Rachel Valinsky is a writer, editor, and curator based in New York. She currently works as Managing Editor at the Center for Art, Research and Alliances. Rachel is co-founder and Artistic Director of Wendy’s Subway, a non-profit arts and literary reading room, writing space, and independent publisher in Brooklyn, New York. Her writing on performance, dance, and moving image work has appeared in Artforum, Art in America, BOMB, frieze, e-flux criticism, and elsewhere and been published by the Berlinale International Film Festival, Danspace Project, Sternberg Books, among others. Her translations have appeared from Semiotext(e), Editions Lutanie, Pluto Books, Editions 1989. Rachel teaches courses in art history, performance studies, art writing, and critical thinking at New York University and The New School.

-

This text is featured as an introduction to the book Rene Ricard 1979-1980, published by Editions Lutanie in March 2018.

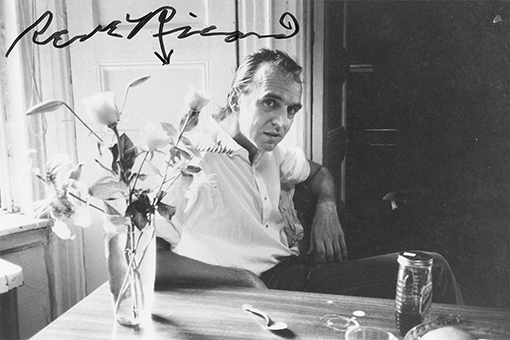

Picture: Rene Ricard, July 29, 1986. Photo by Allen Ginsberg, courtesy Stanford University Libraries/Allen Ginsberg Estate.