Introduction to God with Revolver, by Rene Ricard

Raymond Foye

Rene once told me about his visit to the Andy Warhol survey at the Institute for Contemporary Art in Boston in 1966: “I sat in front of a large flower painting and planned out my entire life.” He was nineteen.

I always felt close to Rene because we both grew up in and around Boston, a rather provincial city in those days, with a small but important counter-culture. The two dozen colleges there provided a steady supply of young blood, which Rene always took good advantage of, crashing in the Harvard dorms with occasional boyfriends. Boston and Cambridge are separated by the Charles River, which you could cross on the MBTA train, or walk the three miles if you wished to save the quarter. They were very different places so it was a good arrangement: if you got bored with one scene you could jump over to the other. The fifteen-year-old Rene hooked up with his first mentor, Prescott Townsend (1894–1973), founder of Boston’s modern gay rights movement. Soon he met John Wieners, Steve Jonas, and Ed Hood (with whom he appears in Warhol’s Chelsea Girls, 1966). Gloucester and Provincetown were the outposts. It was a world.

After seeing the Warhol show at the ICA and making a few connections in Andy’s scene, Rene moved to New York and began his apprenticeship at the Factory and Max's Kansas City, where he laid the social and aesthetic groundwork for his early poems. His milieu was always the art world. He disliked poets and the poetry scene— not enough glamor or money. His poems of the late ‘60s and early ‘70s are collected in his first book, 1979-1980, published by the Dia Art Foundation and edited by Gerard Malanga. There were subsequent books being prepared in the Dia poetry series, including John Wieners and Angus MacLise, but Rene’s demands were so costly and onerous these volumes were abandoned, and his ended up the only book in the series.

The 1980s were a fortunate time for Rene. Painting, his great love, came roaring back, and he could claim his rightful position as critic-flâneur. The merging of art and capital that Warhol foretold had begun. It was a lucrative period, and Rene was not shy about claiming his share of the spoils. Champagne flowed in the expensive restaurants of New York, and Rene dined out nightly on his wit and influence (his models were Whistler and Wilde). Behind the bravura he was also careless, undisciplined, and lacking in self-esteem. For one who was not built with brakes, this period was destined to end badly.

By the end of the 1980s he was in dreadful shape. After burning down his apartment he was sleeping on the subway, unwashed, malnourished, with skin conditions. He was sometimes psychotic, talking to people who weren't there. He was also smoking crack, and having unsafe sex with Times Square hustlers. That he survived this period is a miracle. It was during that time we assembled this book. I was never entirely satisfied with it, but I felt something had to be done, as I was afraid it would be his last. In those days Rene would drop in on friends, collapse for a few hours, borrow money, and be off again. But he often would leave behind poems, scribbled in a book, on the wall, or on some painter's canvas. God with Revolver was compiled from these scraps, which I gathered up in his wake, thanks to Richard Hambleton, William Rand, Robert Hawkins, Francesco Clemente, Brice and Helen Marden, and others. I was always frustrated there wasn't more, but I took what I could get.

Francesco Clemente and I met a few times a year to discuss possible titles in the Hanuman Books series we published in Madras between 1985 and 1995. Always at the top of our list, Rene agreed to be part of the series only if his were a full-sized book, something that violated the whole premise of the project, based as it was on the miniature format. This sort of contrariness was typical of Rene, but he had a good point: he did not want to see his carefully crafted lines broken after every fourth word. And his lines were carefully crafted. He was an expert in metrics and verse forms, and although he doesn't adhere to any formal models, they always underlie his work.

The final edit of this book (revisions, deletions, sequencing) took place over one long, harrowing day at my apartment in the West Village. Rene dropped by unexpectedly and I brought out the folder of poems I'd been collecting. The timing was auspicious because we were sending off the next group of titles to India in a few days. Rene was quite high and was accompanied by a street tough, a hustler he'd picked up on 42nd Street. The two of them smoked crack from a small glass pipe, the acrid acetone fumes filling the apartment. Then they would disappear into the bathroom to have sex.

As if this weren't enough, at one point Gregory Corso stopped by with his friend and translator George Scrivani, who traveled to India every year to see the books through the production process. Normally Rene would not have tolerated another poet, but he and Gregory admired each other's work. This was important to Rene, because with the exception of Robert Creeley and John Wieners, he felt his work was not accepted by the previous generation, and mostly it was not. His confrontational and abrasive style never made him many friends.

Gregory had never smoked crack before and was uncharacteristically trepidatious: “I hear if you smoke it once you're hooked for life,” he said. “Yeah, so...” Rene replied. Gregory took the pipe. “It looks like your literary Parnassus is quickly turning into a crack party,” Rene sneered, never missing a chance to tease me about my abstemious ways. At one point I managed to get him to eat something, a salad made with mâche. He'd always heard of mâche but never had it. A little thing like that could make or break the day. Suddenly he was in a good mood.

We discussed the book cover and Rene produced a color photograph taken at a Penn Station photobooth. In the photo he was wearing a replica Civil War cap (Union side), which he'd purchased in an East Village boutique, and wore for much of that decade. He was also wearing a black motorcycle jacket, and a white shirt with a black crew neck collar which he'd swiped from me a few weeks earlier. It was an expensive item I'd purchased at the Charivari shop on West 57th Street. Rene always had a good eye for quality.

You had to come to Rene through his work, and you had to admire the work enough to endure the abuse. If you were lucky you were eventually admitted into the V.I.P. room. I always considered Rene lazy, and resented him for it. To watch someone throw away a god-given talent is a difficult thing. But now I think I understand that by refusing to treat poetry as a mere literary exercise, he kept the poems as close to himself as possible. He had no interest in writing anything that was not of the essence. The themes of passion and betrayal that drove his life also drove his poems. In the three decades since we published this book, I have reread it countless times. It has become one of my favorite books of poetry. This book is full of small masterpieces that I continue to puzzle and marvel over. Nearly every one of them is memorable, whereas I can hardly call to mind a single poem from the collected works of many of his contemporaries.

The poems of the Greek Anthology were his primary model and ideal, and the verses in God with Revolver are likewise satirical, elegiac, homoerotic, epigrammatic, and by turns elegant and crude. The erotic is the door to the divine; God and lover are one, and his is not a Christian god of love. This is the subject of the title poem in this book, “God with Revolver.” Years later Rene told me he felt this poem foretold the events of 9/11, as if through the personal he intimated the global.

In the 1990s Rene's life stabilized. I think he realized that if he continued to live like that, he would soon die. He did have an instinct for self-preservation after all. He got a studio apartment in the Chelsea Hotel, through the largesse of its then-owner, Stanley Bard, and his friend Rita Barros, and began a successful career as a visual artist, painting his poems. Almost daily I encountered him in the hotel, buoyant, elegantly dressed, so different from that earlier haunted incarnation.

In 2003 I commissioned him to make me a painting based on one of my favorite poems in this book, “Edit View.” The filmic title actually refers to the view from the window of his friend Edit DeAk's Soho loft. He is preparing to go out for a night on the town. The unit of time in the poem is the pack of cigarettes, like sand running through an hourglass. “What is square time?” I asked him. “Square time,” he repeated flatly. (He hated questions.) A few days after he delivered the painting, he brought me a smaller canvas with a coda that read: then time eats its children ... and we forget. He told me the poem was really about Kronos and Lethe, the personifications of time and forgetfulness in Greek myth. At a time when everyone was young and immortal and living for the next party, Rene had an awareness of how it was all slipping away. He was well acquainted with Oblivion.

All his life Rene had an abiding love of French culture. His favorite poets were Villon and Verlaine, and he translated both authors for his own enjoyment. Like Kerouac, he grew up in a French-speaking community in Massachusetts (New Bedford). One of his childhood friends told me how in the seventh grade Rene would constantly correct his French teacher. He would be thrilled with the thought that his works would find an audience in France. This is his second book published by Éditions Lutanie. I would like to express my gratitude to Rachel Valinsky and Manon Lutanie for their commitment to his work.

Raymond Foye

Woodstock, N.Y., 2022

-

Rene Ricard was an American writer, artist and actor born in 1946 in Acushnet, Massachusetts. After a troubled childhood, he fled to Boston as a teenager where he came into contact with literary and artistic circles. At the age of eighteen, he moved to New York City and became a central figure in the city’s art and literary scene. Ricard appeared in several films by Andy Warhol and continued to act in many independent films throughout his life. In the 1980s, he wrote two major collections of poetry, as well as important essays and articles, some of which were instrumental in launching the careers of artists such as Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat (he wrote the famous article “The Radiant Child” in Artforum in 1981). Beginning in the 1990s, he developed a pictorial body of work and exhibited his paintings in various galleries in the U.K. and the U.S. He died in New York in 2014.

Raymond Foye (b. 1957, Lowell, Mass) is a writer, curator, editor, and publisher based in New York City. He worked as an editor with City Lights Books, Petersburg Press, and Beatitude magazine, and was a contributor to the punk zine Search and Destroy. He edited Bob Kaufman’s final book of poems, The Ancient Rain (New Directions, 1981), two volumes of John Wieners’ work for Black Sparrow Press. In 1985 he founded Hanuman Books with Francesco Clemente, publishing fifty books in that series. Foye co-authored Francesco Clemente: Three Worlds (Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1990) with Ann Percy. He was the photography curator to Allen Ginsberg and worked extensively on publications and exhibitions with writer and curator Henry Geldzahler, whose papers he catalogued and curated for the Beinecke Library at Yale University. From 1990 to 1995 he worked as director of exhibitions and publications at the Gagosian Gallery in New York. As an independent curator, he has organized exhibitions with numerous galleries worldwide, including Planthouse New York, James Cohan Gallery, Galerie Jablonka Berlin and Cologne, Thomas Ammann Fine Art Zurich, Studio Raffaelli Trento, and Tobias Mueller Modern Art in Zurich. At present, Foye is an advisor to the estate of painter and filmmaker Jordan Belson and is preparing a comprehensive monograph on his work. He is the literary executor of the Estates of poets John Wieners, James Schuyler, Gregory Corso, and Rene Ricard. He also serves as an advisor to the Bob Dylan Center in Tulsa, Oklahoma. His imprint Raymond Foye Books published Selected Poems by Eric Walker in 2019. In 2020, he received the American Book Award for editing the Collected Poems of Bob Kaufman. He is a regular contributor to the Gagosian Quarterly and a consulting editor with The Brooklyn Rail.

-

This text is featured as an introduction to the book God with Revolver, by Rene Ricard, published by Editions Lutanie in June 2022.

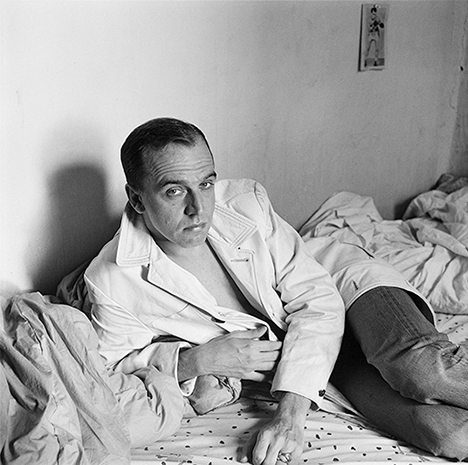

Image: Rene in his apartment, E 12th St., NYC 1980. Photo: David Armstrong, courtesy David Armstrong Estate, 2022.