God's Cruelties - Afterword to God with Revolver, by Rene Ricard

Patrick Fox

ANDY DIED TODAY AND TOOK

ALL THE FAME WITH HER

February 22, 1987 Rene Ricard

Rene Ricard was a great actress. Like Nicole Kidman, Rene’s eyes would go bloodshot before ever shedding a tear, calling upon his capillaries for emotional emphasis. Though Rene rarely “performed,” when she did, his greatest “performances” concealed a history of scars left by the switchblades of verbal abuse, welts from the lacerations of emotional undermining, and dark subcutaneous bruises from a childhood of sexual abuse, which Rene, like many, would vent as anger or, in his case, a biting meanness. His pain was easily accessed, it was just below the surface, obfuscated by his whip-sharp wit, flamboyant charisma, and his above-the-fray demeanor. Rene’s pain could be utilized effectively; what he revealed was not based on cheap sentiment or superficial emoting, nor was it an “acting technique.” Yet these performances— probably the wrong word, but not entirely—were small, reserved for his closest friends and those he considered confidants. When called upon to witness the physical manifestation of Rene’s interior pain, tears were expected, but often seemed to miss their cue. They would appear late; the moment had passed. We’d watch him park it in bloodshot, a fixed emotion.

Over the years, I was privy to Rene shedding many tears. Once, on his deathbed, at Bellevue Hospital. The first time was the night we met, sitting on the floor next to a speaker on the edge of the dance floor; he recounted how he had been abandoned by the great love of his life on Christmas Day. His cornflower blue eyes, distant and steely, revealed that he had been wrecked by this seismic, life-altering rift. Explaining why he was misunderstood was when those red cracks began to appear. “He’s told everyone I’m a monster, but I’m not the monster, in fact I’m still a little boy, I mean, I’m the same as I was as a young boy: I’m just a poet.” Cue the tears…!

In the brief years that followed, Rene and I shared two things most significantly. First, a love of art—still discovering insights I learned from Rene, I cannot begin to explain how much he taught me about art, art history, painting, and beyond. I watched him see, and saw how he saw differently than anyone I’d ever known, his skewed, visionary outlook the backbone of his “invented scholarship.” Rene told me that I helped him discover new artists, and would introduce me by saying, “his gallery is at the epicenter of NYC’s avant-garde.” We were invigorated by one another and inspired by the work of a generation of mostly younger New York artists, several of whose work I remain honored to have brought to Rene’s attention.

The second thing we had in common was our miserable, psychological, post-love damage, (labile, we’d laugh to the point of tears), the emotional debris left in the aftermath of love’s revenge, polluting our brains in the wake of love, which remained, to the end, our most primal bond, it cemented our friendship.

Some years later, Rene shared an extended display of the delayed bloodshot tear-drama, in an exhaustive emotional rollercoaster on the night train from Naples to Rome.

Rene and I left Cookie Mueller, her future husband, the artist Vittorio Scarpatti, and a small group of New Yorkers in Positano in mid-August of ’85 to visit Rome. Our plan was to see Francesco and Alba Clemente; Rene wanted to introduce me to Luigi Ontani; we wanted to spend time in the Vatican; then see as many Caravaggio altarpieces and investigate his life in Rome, if possible. Arriving just before dusk in Naples, a taxi outside the train station drove us to Hotel Vesuvius, where Rene talked the desk into letting us stay the night. Naturally, we went out and stayed out as late as possible; the hotel wake-up call left us barely enough time to check out. Leaving our bags with the concierge, like vampires we tooled around in the too too bright, overheated August daylight, making our way as fast as we could, scurrying like street rats from shade to shadows, eventually making our way to the cool interior of the Museo di Capodimonte. A taxi ride and a faster run through the Archeological Museum. Picking up our bags about the time we arrived the previous day, we realized we best head to Rome while we could, where I still had reservations at the Locarno.

Our taxi dropped us off as far away as possible from the train station in Naples while still being able to say that we were dropped off at the train station. “Relax, Patine, it’s Italy, nothing runs on time.” We ran to catch the train, both sweating profusely. We climbed aboard the on-time train, just in time. “Patine” was Rene’s nickname for me. He was the only one who ever used it.

The train to Rome was packed with locals, many with children, some widows traveling alone, and two passengers, one at each end of the train car, who appeared to be traveling with their chickens (thankfully, both exited rather early at different stations). Within half an hour of departure, the interior lights flickered and slowly woke up from their midday nap, intensifying, settling somewhere between an amber and the most unsettling red-orange. Rene was prone to singing made-up songs about his surroundings; he gleefully took up the tune of a Shirley Temple song, keeping myself and a few people nearby buoyantly entertained.

In this synthetic light, straining to be heard, Rene, out of nowhere, began telling me about a book of poetry he had been working on. It had been on his mind to discuss it with me since I arrived in Positano. He wanted to tell me about it because he believed I could publish it through my gallery. Who wouldn’t be intrigued by the prospect? My father had died a little over seven months earlier, and Rene knew he had been a publisher of sorts.

Rene began describing his idea to me with as much genuine enthusiasm as Judy Garland, his ebullience as infectious as Judy’s amphetamine laugh. It seemed simple enough: he wanted his book of poems printed exactly like a comic book, with the same newsprint paper stock, size, and semi-gloss finish for the cover stock. No words on the cover, “Not even my name, just an image.” Simple and, at that time, pretty radical. He began to pitch it as if I was a producer at MGM and he was Busby Berkeley with a movie idea. Thumbs together, forefingers pointed skyward, “COVER IMAGE: WARHOL’S SNUB NOSE REVOLVER. Beautiful. Simple. Iconic. Silver on Black. Right? SILVER/ BLACK. TITLE PAGE; imagine the titles from a film noir. The 3D block letters with long shadows. My name, RENE RICARD, above the title, but small, eh? Now, are you ready for the title? Ready? GOD WITH REVOLVER.” He repeated, louder, “GOD WITH REVOLVER! YOU’RE THE VERY FIRST PERSON I’VE TOLD! DO YOU LOVE THE TITLE? YOU DO, RIGHT?” “YES! I LOVE IT, IT’S GENIUS! I REALLY love the title Rene!” Busby’s still pitching to Louis B. Mayer. “Ok, turn the page, BOOK ONE. Like a Raymond Chandler novel. After reading book one, you flip the book upside down, spine still on the left, eh? Ok, and on the back cover, upside down... BOOM! WARHOL’S SNUB NOSE REVOLVER, AGAIN! BUT THIS TIME THE SILVER/BLACK ARE INVERTED! BLACK GUN ON SILVER!” His voice was breaking into screechy squeals, competing with the children. “Open the cover, and again, RENE RICARD over the title, GOD WITH REVOLVER, page turned, Book Two… you like it, don’t you?” Near giddiness,“We could use the same silver ink used on your business card!” I was in disbelief that he would even consider my involvement. “They’re love poems. They’re the Louie poems. These are love’s poisonous quills. Don’t you think it’s a good idea? Because I really don’t know who else would publish love poems written by Rene Ricard.” I tried to respond but he was too quick, he didn’t take a breath. He thought he noticed me not clinging to his every word.

Now meet the other side of Rene Ricard, a wounded victim spewing venom. Suddenly he lashed out at me because of a misperceived slight. “If EVEN YOU won’t publish it, why would ANYONE EVER want to publish a book of Rene Ricard’s love poems?" He saw red, if he blinked, his face would be a cascade of tears, like a Pat Steir painting. But when he raised his head, he was lurid, deadpan. “I can’t believe you don’t like it.” “I’ll never get another book of poetry published. No one will ever publish GOD WITH REVOLVER.” End scene . . . and tear.

In my opinion, GOD WITH REVOLVER is Rene Ricard’s most honest volume of poetic works. If I had realized then what a masterful book was torturing his psyche, I might have skipped Rome, rushed back to NYC, and immediately began pulling together the necessary whatever was needed to publish GOD, with the Warhol snub nose REVOLVER cover. It was not to be. GOD was not mine to publish. Andy’s REVOLVER wasn’t God’s cover. Recently rereading GOD WITH REVOLVER, I now see Rene’s maturity; it’s Rene hitting his stride as a young poet. Ok, I would not have missed Rome with Rene for all of Venice.

The writing overlaps a year of the “Dia Tiffany” book’s poems. Rene was in his early thirties when he wrote most of these. Is there anything more heart-wrenching, more emotionally terminal than the enraged, cinematic madness many experience after the trauma of being ditched by their greatest love? Rene, downed by love, but not out for the count. Snow White is dressed, and Disney’s blue knock-out-birds circle his head as his “Crown of Proof.” These poems of pain, the experiences from which they are derived, made Rene who he was, and the writer he would become.

Rene delighted in peeking under his Jedd Garet sculpture. He’d lift the hem of the weightless pink lamé cloud. At the pinnacle of this confection sat a blue and white bowling ball, which looked heavy and suspiciously like our planet Earth. Rumor has it that it was lost in Rene’s apartment fire around 1990, when he still lived across the hall from Allen Ginsberg on E. 12th Street. He favored the quiet brute, the tortured armature, resembling a mangled Atlas without human form, and without a fuss, carried the weight of the world. “See Patine, Love is an action. He makes it look sissy easy for Mr. Miss Pink Lamé.” It’s the steel under the chiffon—like in “Grey Chiffon Day,” a term Rene coined as a boy in New England, when the bright cerulean light is merely obscured by the mist.

At Rene’s memorial I said Rene got better with age. Well, he’d be pleased to know that his writing has too. My connection to these poems is not just a teary train ride from Naples to Rome. Years later, when Rene gave me a second copy of God with Revolver to replace a stolen copy, he wrote two dedications:

Rene Ricard

Really I cant afford to let you have this Patrick.

2004

July 16

almost my

birthday.

Translation: I can’t believe you can’t afford this, but you can’t afford not to have this. Then, on the back of a card from Paige Powell, with her instructions “$20 so load that thang and call me” (referring to a phone he was using at the time), he wrote:

Dear—I mean

poor dear Patrick you don’t have this

poor book and

you deserve it

more than anyone

else—and you don’t

remember—but it’s

memorable anyway

Rene

Rene was both the kindest and cruelest of friends; like Nan Goldin said, “We all suffered his barbs at some point. His tongue was an unlicensed weapon. Even those of us he loved could be scared of him. But I always loved him.”

Rene knew he had to be brutally clear about the most sinister and darkest aspects of love, and yet, he rejoiced in the promise he felt in the slightest of flirtatious palpitations, fluttering at the slightest provocation of love, knowing that the shadowed inevitabilities love always provides were part of the deal. Love’s cruel gift with purpose.

I miss him daily.

Fortunately, Raymond Foye was ready, patiently waiting in the wings for Rene to step up and out from the chorus line. Along with Francesco Clemente, they were Hanuman Books, the time was right for them to publish GOD WITH REVOLVER, which went to press about a year and a half after Andy Warhol died. On the cover, Rene in his well-worn Civil War cap purchased in the East Village—it’s in many photos and it’s how Michael Wincott portrayed him in Julian Schnabel’s “Basquiat;” I have lots of photos of Rene wearing that cap, including Polaroids taken in Positano that summer.

“Look, Patine.” I still see a feeble wrist elegantly resolved with Rene’s fingers, the only part of the hand I recognized. Weak yet steadily holding up a sketchbook for me to see the drawing he’d done of the night nurse when I returned from getting supplies. In his darkened hospital room I could clearly see the familiar hand of his line, and how he’d “sketched in” with the unmistakable crosshatching his mother, Pauline, taught him as a young boy. I handed him a PayDay candy bar and said good night.

.

JANUARY 31, 2014, 8:45 p.m.

Rene Ricard died about three hours later.

Pronounced dead at 12:05 a.m. February 1st, 2014

Patrick Fox

NY, 2022

-

Rene Ricard was an American writer, artist and actor born in 1946 in Acushnet, Massachusetts. After a troubled childhood, he fled to Boston as a teenager where he came into contact with literary and artistic circles. At the age of eighteen, he moved to New York City and became a central figure in the city’s art and literary scene. Ricard appeared in several films by Andy Warhol and continued to act in many independent films throughout his life. In the 1980s, he wrote two major collections of poetry, as well as important essays and articles, some of which were instrumental in launching the careers of artists such as Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat (he wrote the famous article “The Radiant Child” in Artforum in 1981). Beginning in the 1990s, he developed a pictorial body of work and exhibited his paintings in various galleries in the U.K. and the U.S. He died in New York in 2014.

Patrick Fox is a writer, art dealer, activist and actor based in New York. He has contributed articles and essays on the subjects of photography, art, architecture, and urban revitalization in various publications and museum catalogues. Before focusing his efforts as a private art dealer in 1999, he opened two public art galleries in New York and later, one in Los Angeles: The Anderson Theater Gallery (1983), Patrick Fox Gallery (1985), and Fox & Howell Gallery (1996). He was first to exhibit friends George Condo, Greer Lankton, David Armstrong, Sue Williams, Bill Rice, Stefano (Castronovo), Alexis Rockman, Robert Hawkins and Rene Ricard. He showed and worked with Bill Rice Kenny Scharf, McDermott & McGough, Jedd Garet, James "Jamie" Nares, Cookie Mueller, Olivier Mosset, Alain Jacquet, and Luigi Ontani. In the 1990s Fox worked as a field representative for The National Trust for Historic Preservation after successfully spearheading an effort to block the demolition of a low rise building designed by Ludwig Meis van der Rohe. He is a member of Nan Goldin’s non-profit advocacy group P.A.I.N., which acts to end the overdose epidemic and the stigma of addiction. He has acted on stage in plays written by Gary Indiana and Terrence McNally and was the sole male cast member of The Ex Dragon Debs. He can be seen in Sarah Driver’s Sleepwalk where he is credited as The Gargoyle and was featured in the now lost 1980’s version of The Three Penny Opera, by Mary Lemley. He’s been cut out of more movies than he can recall.

-

This text is featured as an afterword to the book God with Revolver, by Rene Ricard, published by Editions Lutanie in June 2022.

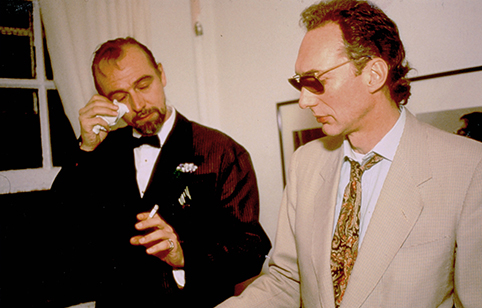

Image: Rene Ricard and Alain Jacquet at Cookie Mueller's wedding with Vittorio Scarpatti, 1987, courtesy Nan Goldin, 2022.