Interview with Tadashi Kawamata by Cerise Fontaine, for Éditions Lutanie, Paris, May 2012 (extracts)

Cerise Fontaine: I read somewhere about a Japanese tradition of ritually tearing up and rebuilding wooden houses, is that true?

Tadashi Kawamata: There is a very special shrine, in Ise, which is torn up and rebuilt every twenty years. It’s huge, you know, not just an average house. But there is this idea of freshness and renewal in Buddhism and Shinto – Japanese animism – and in order to preserve this quality of freshness, the shrine is always changing. But the style and form never change. It’s always the same form, same style, sometimes even the same material, but it changes every twenty years.

What do they do with the material that was used in the old shrine?

This is very interesting. They chop it into very small pieces. Ise has many worshippers, who regularly come to pray and donate money to the shrine. And they receive chopsticks made from the old shrine. So every twenty years they get new chopsticks.

And they worship them?

Yes, because they are part of the shrine but also they become a part you can eat with. And because what you eat becomes a part of the body it is in some way blessed, which is a very old religious idea. And so they use the chopsticks in everyday life. The posts are enormous, like this [indicates 40cm], maybe bigger, and then they are cut up delicately into chopsticks for the people.

And when you’re done with the planks in your work, what becomes of them?

I always have a plan when I’m doing a project to alter the thing that we are making, to recycle it, to make it a part of something else. I used to get scrap material and just throw it away after I was finished, even with new timber. Now I recycle it for other projects. And sometimes when I get an offer for a project they already have a plan for how they’ll use the material afterwards. Sometimes they make a small hut, maybe a garden shed, and they already have it in mind. I always need this sort of after-project, to know how the project will continue in this way. Because this is part of the project too, you know. For me, building up and building down, they aren’t so different.

Maybe you can make chopsticks out of your work!

It’s too much cutting! And it’s too religious to make chopsticks. Maybe a bookend, or chairs, benches. That would be easier.

I wanted to ask about the Mono-ha movement, you said elsewhere that as a student you didn’t like it…

Did you know Mono-ha? They were around in the 1970s, a Japanese movement made up of artists. It was similar to Arte Povera and when I was a student a few of our professors were part of Mono-ha, which was why I was a bit against it.

Because they were too powerful?

Yes, and although Arte Povera and Mono-ha have different styles they are in some ways quite similar. Simplicity of the materials… I don’t really like attaching too much emotion or sentiment to a material – they feel, you know, a stone has some extra kind of meaning… But for me a stone is a stone. I’m more dry, I’m more cool. And I never fell into this way of thinking. I like just the space, because it’s just a space in itself, nothing more… For Mono-ha, when you place a stone, the space becomes tense with it. Of course, this happens sometimes, but the stone is just a stone, just like a layout. So, the layout is my ‘stone’ in some way. I can choose any arrangement, which is easier, less sacred, without any deep insight into the emotional side. I’m very practical. This is the only way I could survive, otherwise they [the layouts] might destroy me.

Maybe we can talk about ‘Under the Water’ now. I was very curious about the contrast between the feeling of peace you described and the violence of the impression it made on me.

I think both are at play in ‘Under the Water’. If you look at the installation from above, at the image of all the scraps floating on the water, they are just floating, immobile. It’s very quiet, a real silence. But if you were looking from under the water back at the sky, it would be quite a different feeling. This time, the installation was both in a courtyard – and so seemed to be surrounding the building – and in the gallery. They are both small, which meant space and material restrictions. But in my imagination floating in water means being without limit, being like the sea, which reminded me of these scraps, silently floating. I knew that I needed both feelings. It is quite violent, and most people don’t get to see it from the second floor, where it appears completely flat – as though the gallery has been flooded – which is something I wanted. And although you might only get one aspect, you can imagine floating on the ocean like this and imagine, just after the tsunami, these things floating quietly, not moving. Because a tsunami is extremely aggressive and yet after it is over, things move back to the sea, slowly, and smoothly. This is such a contrast, to have the sea suddenly so violent and then return to itself and become tranquil again. You know, I saw all the documentary films, and you can’t help but feel so hostile towards this violence, but when you go back to the water, to the sea, all that is left is a deep feeling of sadness, because it all just comes back to this silent sea. And people can’t do anything. Something that lasts only half an hour. It comes and it recedes. That’s all. And yet it changes everything. I was in Tokyo at the time and I saw what it did, and even in September, October, I was still feeling… I’m not a writer… and if I was in Tokyo I would be volunteering, but I’m in Paris. And what I make does not help people in that way, but it’s how I go about understanding it. So the gallery asked me to create an installation and from this feeling of the tsunami came ‘Under the Water’. And even now, I haven’t stopped feeling it and each time it’s a different thing.

Do you think you will re-act this installation in different places? Do you already have propositions from other places, other galleries?

I have a project in Tokyo at the moment, which is going to be a tower and I’m thinking about using scrap material for this one. It will be the second part of ‘Under the Water,’ which I hope will come to Paris. I still don’t know if it’s going to be realized or not. After the tsunami there was a huge amount scrap material from destroyed houses and infrastructure, I don’t know how much, maybe a hundred thousand tons, it’s huge. This is one of the major problems we have, to make it all disappear, you know. All the cities and prefectures have to work together, but it is very sensitive because at the same time, people don’t want it to disappear. This stuff was a part of their lives, you know, their memories. So even the fact that I am trying to make a tower with this scrap is sensitive. I have already had reactions from some people in the tsunami area who don’t like the idea. To them, it’s a show that will exhibit their homes, a piece of their house. So it is still very delicate at the moment but I think I will make a tower in Tokyo to show how it will work and bring it to Paris, because scrap is always floating in and back out to sea. It will be like orienteering with the material, the tower will follow a similar path. But after Paris, I want the tower to go back to its origin and stay there. So, we’ll see what happens. It’s still very delicate.

So your idea is to use the scrap that is still there, not the one that are floating on the ocean. I thought you wanted to collect what is floating right now in the ocean and from this build the tower?

No, no. The scraps floating in the Atlantic are more metaphorically interesting, because in a year they will have floated back to the original place. So what I imagine is the project also moving naturally, so that people realize. Because people try to forget a big incident like this, but the material itself will reappear. I don’t want the tower to be destroyed afterwards; I want it to keep a memory. It’s not like I’ll pick up scrap from the ocean and just put it in place like this. I like a more metaphorical method. I think it will be realized this year.

Do you know what you want to call it, the tower?

I always use the name of the place for my projects. But I still haven’t received permission. For the moment, it’s called ‘Tokyo in Progress’…

And so, would you rebuild the ‘Under the Water’…?

I don’t know. ‘Under the Water’ was really interesting, both the title and the concept, but I wouldn’t keep the same structure, you know… Do it in a different way, but I like the idea that we are always looking at the sky from underwater.

That was really beautiful, to be able to see the sky from within the gallery through the installation…

But you had worked on similar things before, for example in Berlin.

Yes, two or three times, because I really like the kind of tension it produces. I made one installation in a former coalmine town in Germany, where the museum used to be the bunker, so it had 2-meter thick concrete walls, so the building itself felt very constrained. Then I made another ceiling, which added to the tension, because under a 2m ceiling people had to lean and bend back, so the project seemed to combine the pressure of the bunker, of the coalmine, and of this ceiling, all mixed together. And of course I made the chairs in Delme, which was in a synagogue, so it’s a really recognizable place. The ground floor and the first floor are different: the ground is only for the men and the first floor for women. So it’s a divided space. The chairs floated in between. There were no chairs on the ground floor, none on the first floor; they were floating in between and you could see through these floating chairs to the first floor. It’s similar to ‘Under the Water.’

We were also curious about the slides that you projected in the gallery. We wanted to know first what were these images, where do they come from, have you been collecting them for a long time?

I have been collecting them for a long time, yes. Initially it was just the newspaper and as I would read I would cut out images and make scraps.

Do you have albums?

Yes, I don’t know how many, but I’ve been doing it for ten or fifteen years. And I’m still doing it. And the scrapbooks are all still in Tokyo. There was an exhibition I did in Tokyo of slides. One in the Mito Art Tower, which was a big installation made from newspapers. I piled up five tons of newspapers. They ask for an installation, but only inside, not out. So I found my material – and five tons is roughly the amount for a city of Mito if in one day everyone read one – and I put it in the museum. It’s not wood; it’s a new material. And because I was already scrapbooking from the newspapers, I showed the photos as well. It was a sort of dialogue with the accidental side to my work. I don’t know why I am so fascinated by these kinds of photos… it’s really interesting, and quite exciting in a way. Of course, there are these disasters, these terrible things happens and perhaps what is really strange is that after a tornado or a car accident, you don’t see very much.

You never see bodies.

You don’t see the bodies. Because these are mostly from Japanese newspapers and the images are controlled. I knew this of course. We never see dead bodies in the newspapers and this kind of control is well known. But for me, I’m more fascinated by the structural thing, not necessarily the social or political implications of war, for instance… I am fascinated by the way that the destroyed thing turns out, the strange structure it becomes. So I think outside of this image control in a different way, which is quite interesting.

So this is the link between those images for you. Images of your work and of a car accident and of a nuclear explosion… It’s the structure.

Yes, the controlled and un-controlled.

(…)

About the material – we just talked about work that was made out of newspaper, but most of you works are still made with raw wood, and when we think about your work it’s what comes to mind most immediately, but you say often that you don’t care much for raw wood in itself, so would you have used any other material?

You see… I don’t want to think too much about material. I think once you decide, you just continue with it. It is easier not to think about the material. If you’re looking for material and you have to think, ok, metal or stone or… this is too complicated. So I think I started working with wood because, I don’t know, maybe because I was studying painting and not sculpture, not architecture. And a painting, it’s a canvas and a structure. And my first installation I just stood the canvas in the space, the second I removed the fabric, so only the structure was left, which was really the first of my installations in wood. And I’m always recycling you know, so I use the same wood but with a different structure. It’s for economic reasons too, wood is very cheap and it’s everywhere. Standard size wood is so easy to find and everyone can handle it, everyone can drive in a nail, or cut it, even small kids. And people like this, it makes for a very open material, you know, and it’s so global and cheap, which is really good for me. I don’t need to transport it anywhere; I can always get it on location, even the recycled stuff. So it’s really the best material for me, though of course sometimes I’ll use newspaper, or metal sheds, and chairs, of course, because these are systematic elements. But of course, chairs and newspapers are also made from wood.

And you always leave the material raw, you never want to paint for example, after you build it?

Originally, I painted the structures white. Or I had a show in a gallery and I left some raw and I painted the others, as though I was erasing them, because sometimes it’s too much, it’s too tense, so I paint it and it can disappear. But yeah, mostly I don’t paint anything; I just use it as I find it, a sort of natural mosaic.

About your work here at Beaux-Arts, could you tell me how you teach?

I think student by student, so if they have a question, I just talk to them about it, and if they want to show something, I go to look at it and I give them some criticism, so it’s really simple actually. I’m not constantly in front of the class, teaching like this. The students make projects and if they have problems or ideas, we discuss them. So it’s mostly discussion. I think you have to be careful teaching students art, because I don’t want to push my aesthetics on them, nor criticize them too much. I have to respect their feeling, their sense for the material, so that they get the most out of the work. It’s much easier to destroy something, to say, “I don’t like your work,” but this is pointless. Because art isn’t one plus one, you know, it’s hard to evaluate. So if a student wants to be an artist, you have to be able to respect them and to take care of their sense of their own work. It’s also why I don’t like having too many students in my class.

(…)

You talk a lot about this book, Architecture without Architects, by Bernard Rudofsky…

It was a big hit in the 1960s and 1970s. This book was huge. For most architecture students, but maybe not so many students in art or sociology etc., it was something you looked at all the time. For me, I got onto this book through a friend and was totally fascinated. I even visited some of the places in the photos. It’s really intriguing, this vernacular architecture. And for me, this was art. I discovered Facteur Cheval around the same time, when I was still a student. And it seemed to me that artists are like that, they do what they want even if everyone thinks they are crazy. And Facteur Cheval is more a religious figure, but at the same time his art is quite mad, and this really interested me. Even discovering the way homeless people build their sheds was a revelation to me.

Your main inspirations have been from outside the art world. Are there artists who have influenced you?

Yes, when I was a student I was fascinated by land art, especially Gordon Matta-Clark’s work. He was really the only one at that time working in the city or the town, not in a huge park or the desert. There was Smithson too, but he was more focused on ideas about society. So Matta-Clark I found really interesting. Sometimes working with the landscape is too romantic, to work with these huge spaces can feel super-optimistic, super-romantic and I don’t like it so much. I like art that feels complicated, like something has happened, that’s when I go for it. I really like complicated things and it’s why I like Matta-Clark. I’m happy to be published after Gordon Matta-Clark!

Your current projects are ‘Tokyo in Progress’…?

I have a couple of projects at the moment. Actually, I just finished one in Belgium, in Ghent and now I’m working in Lyon along the riverside, and there are a few projects we will do over the summer, from August to October. Next year I might do something in Parc de la Villette, so I’m still going. It works that way, someone sends me an email and we work something out.

What’s your process of working? Do you work with sketches, writing, models…?

Once I get an offer to work somewhere, I start by visiting the place. Then I gather some information, maps, photos and the rest, and I start to make sketches and from that I create a large and very general proposal with a few different ideas. If they accept I start on more precise mock-ups, drawings etc. This is how I always do it. It usually takes one year, sometimes even three. Actually, the truth is, the first impression always stays in your mind, so you have to go to the place with nothing already in your head, with no preconceived image. You have to just go there, get all the information and then go back to the hotel and sleep. And something sticks in your mind. And this image is the strongest, and usually the most original too. And I’m interested in this way of doing things, to go somewhere without any information. I just walk, maybe get a coffee or something, and when I get back to the hotel I have this feeling of wanting to make some sketches. So the first impression is the most important. And if it is strong, later on the project will also be strong. With the project in New York, on Roosevelt Island, I had first seen the building totally abandoned in this area and I was fascinated. But I didn’t know what I was gonna do. So I was thinking, thinking. Thinking about why I was so fascinated by it. And then the idea for the project just came to me. I think I spent two or three years building the first proposal, working out how I could do it. Because I have no connections, no contacts. So I start fundraising, speaking with people and then I started working with an independent curator [Claudia Gould], who’s now the director of [the Jewish Museum in New York City]. Before she was working as the coordinator of the studio program in PS1. We met early on. We made a proposal and worked together to get all the permissions. We spent seven years working on it before it was realized. And then it took six months for the permissions, three months for the construction, and one month for the exhibition, which could only be visited by appointment. And after one month it was destroyed. That's it.

How did you discover the building (on Roosevelt Island)?

[Indicates] So East River is here, Roosevelt Island is here, and PS1 is here. Each lunchtime I would go up on the roof, and one day I was eating my sandwich and I saw it. From then on I was curious about what it was, what kind of building it was. And one day I went there. Because it’s all closed up I just jumped over the fence and walked around inside. It was a really wonderful thing.

Does it sometimes happen that you’re uninspired by a place where you’re invited?

No, I think almost never. Most of the time I’m inspired straight away, from the sight of the city or the location, the people as well. The location is so important. And this first impression. Especially that, because I don’t have an image in my head beforehand. And perhaps if I didn’t find anything, if I didn’t have an image in my head, it wouldn’t be possible to make anything.

But it has never happened yet.

No. I always find some piece of inspiration.

-

Born in 1953, Tadashi Kawamata is a Japanese artist who lives and works in Tokyo and Paris. He often works on in situ interventions, grafted onto existing architecture using wood and salvaged materials. His work has been shown in many international institutions such as MAAT, Lisbon, Pushkin Museum, Moscow, the Thurgau Art Museum, Switzerland, the Centre Pompidou in Paris and Metz, the Toyosu Dome in Tokyo, the HKW in Berlin, the Serpentine Gallery in London, the MACBA in Barcelona; and also during numerous art biennales such as the Venice Biennale, the documenta 8 and IX, the international Biennale of São Paulo, the Skulptur Projekte Münster, the Sydney Biennale, the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale in Niigata, the Shanghai Biennale, the Busan Biennale, and the Helsinki Biennial, among others. He worked as a professor at the Tokyo University of Fine Arts from 1999 to 2005 and has been teaching at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris since 2007.

Cerise Fontaine is a publisher, editor, and translator. She has worked for various art publishers and galleries such as Éditions Lutanie, MoMA, Perrotin, Fondation Luma, Cahiers d'Art, Cahiers du Cinéma and Gagosian. She is a co-founder of the Icelandic children's book publishing house AM forlag.

-

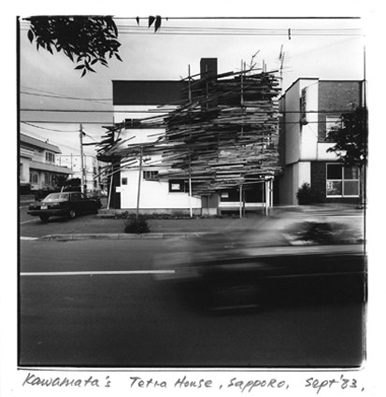

Picture: Shigeo Anzai, 1983