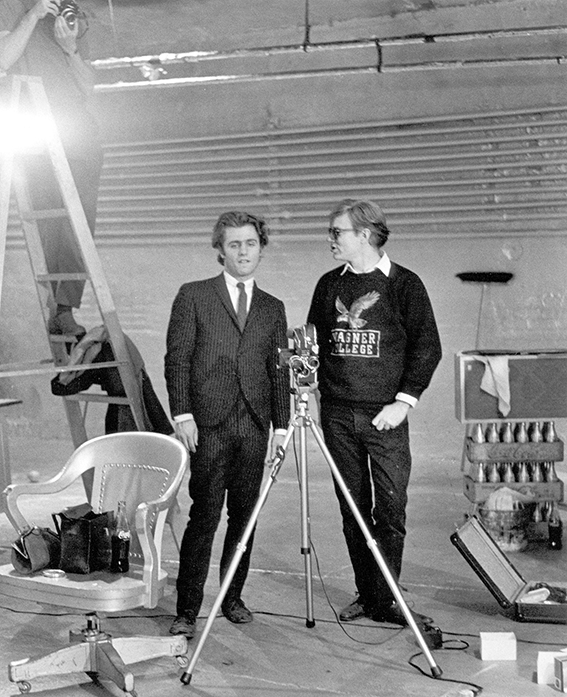

Gerard Malanga & Andy Warhol conferring on a camera angle for Andy's "Kiss" series, 1965. Photo © Archives Malanga.

A conversation between Gerard Malanga, Manon Lutanie and Raymond Foye, on Rene Ricard, recorded in Hudson in 2022.

-

Last summer, Rachel Valinsky, Sean Vegezzi and I met in the early morning outside Sean's building in Brooklyn, and drove to Hudson, New York, to visit American poet, filmmaker and photographer Gerard Malanga. Gerard had agreed to talk to us about his friendship with Rene Ricard, which corresponded to a period of great effervescence in his life, when he himself was working with Andy Warhol, performing with the Velvet Underground, and shooting his first films.

We got lost, arrived late. When we found the dark green-painted wooden facade on a quiet Hudson street, Gerard welcomed us into his living room, where he was sitting with our friends Raymond Foye and L u m i a—his cat Odie asleep by the window. It was a sunny July day, and after the conversation, we went for a walk along the river, then headed back to the city in the fading daylight.

-

Manon Lutanie: Thanks a lot for receiving us. I would love to hear about what your life was like when you first met Rene Ricard.

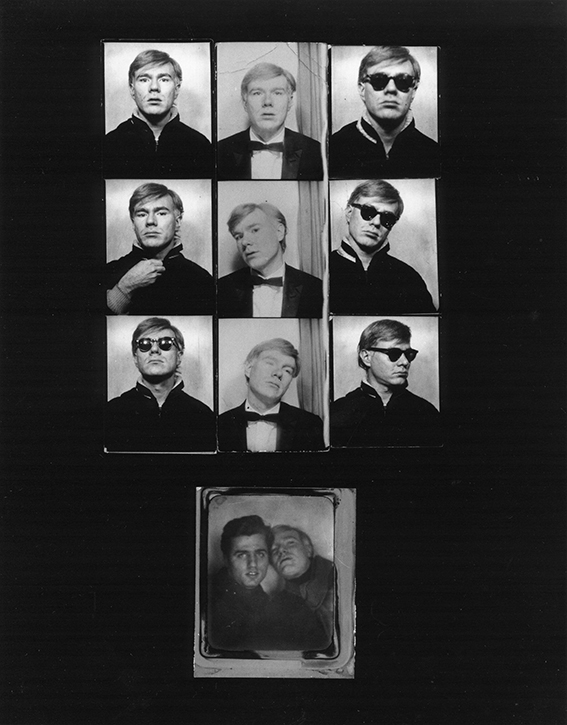

Gerard Malanga: I met Rene probably around spring of 1965. I was working with Andy Warhol, as Andy's assistant. And I happened to be at the Factory one day, by myself, when Rene showed up. I always remember the first thing Rene said to me was: “I came to seek you out.” And I thought that was very funny. He didn't stay too long, but I was very curious about him. Then I was off to Paris for the opening of a show of Warhol’s flower paintings, and when I came back, Ronnie [Ronald] Tavel had written a new script for Andy Warhol, for a film called Kitchen, with Edie Sedgwick. I asked Ronnie if he could write a part in for Rene, that didn’t have to be a speaking part. Rene ended up being an extra in the movie, the house boy. So he was almost like the centerpiece, but in the background. And that was for seventy minutes. He was washing dishes in the sink. I don't remember distinctly how Rene felt about being in the movie, but he seemed to enjoy it. That was really good. That worked out quite well. I didn't see too much of Rene in 1965. I got to see him more maybe a little less than a year later.

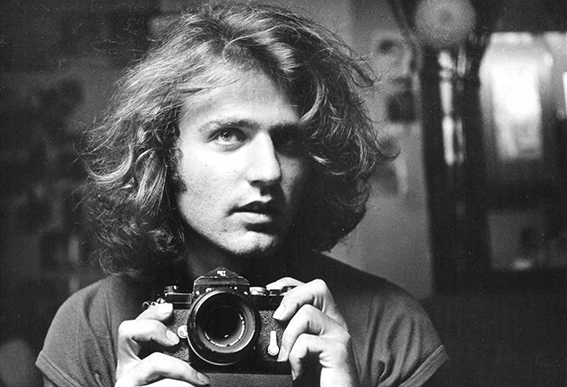

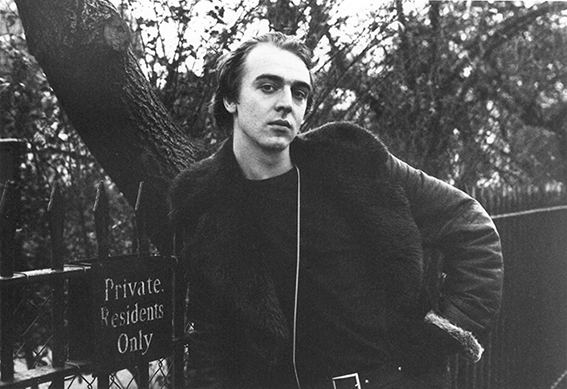

Self-portrait, 1971. Photo © Gerard Malanga.

Manon: Could you describe how he was at that time, physically—how he looked?

Gerard: Well, he was a young Rene. He was thin, he was tall, he was cute. He seemed earnest about wanting to do something, but I don't think he knew what he wanted to do.

Manon: I am also curious about you, at this time. What were your days like?

Gerard: My days in New York City… There were a lot of parties to go to, art gallery openings, meeting interesting people. There were days when I was very quiet. There were days when I was at the Factory. There wasn't anything that was actually the same. There was no routine, as it were. I was also writing at the time.

Manon: You two were so young.

Gerard: In 1965, I was 22, and I think Rene was 19 or 18.

Manon: He wasn't so far away from his childhood and teenage years. Was he speaking about that?

Gerard: Just a little bit. When he was living in Boston, he was sleeping on people's couches because he didn't have a place to stay. I believe he was making money posing nude for art classes at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts school. I don't know what else he was doing, but he seemed a little strung out, so he perhaps brought some of that energy to the office, and a feeling of despondency and searching for something to do with himself.

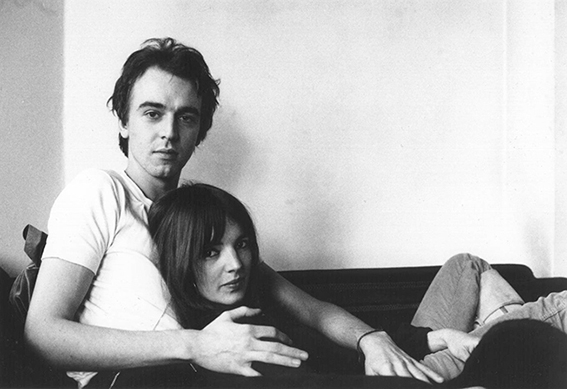

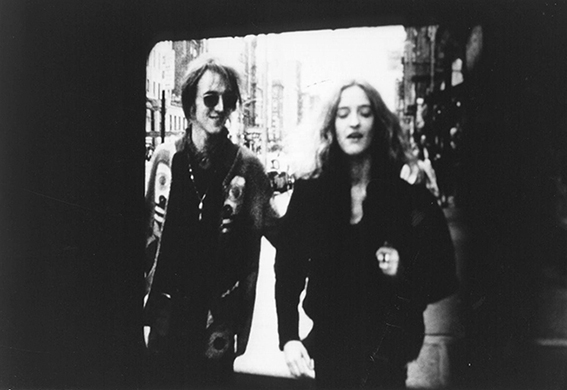

Rene Ricard and Delia Biddle, 1972. Photo © Gerard Malanga.

Manon: What was special about him at the time?

Gerard: He was a good raconteur. He could tell stories. He could be very amusing, very funny, but the kind of amusement that hinted at something behind it, a certain kind of intelligence.

Manon: In your as-yet unpublished autobiography, you wrote a chapter about your relationship with Rene, in which you start by saying that Andy Warhol felt somewhat threatened by or worried about Rene. Could you tell me more about what you witnessed and understood about their relationship?

Gerard: Well, Andy was very insecure himself on a certain level, or even intimidated by people who were really smart. I mean, Andy was a very reticent person. He was very shy. He wasn't very good at expressing himself. Rene was extraordinarily good at expressing himself. So Andy may have felt threatened by Rene on that level, on an intellectual level. It took a while before Andy would probably… During the entire period from 1965 to 1967 or ‘68, Andy probably never really changed his position about how he felt about Rene.

Manon: And do you think it changed after that?

Gerard: Not really, no. Andy never became a close confidant of Rene or a friend—even to me. That’s the way Andy was.

Manon: This makes me think of The Andy Warhol Story (1966), Andy Warhol’s film which has now disappeared, in which Rene played Andy Warhol.

Gerard: It can be seen, it still exists. It perhaps hasn’t been digitized yet. It's probably in the archives of the Andy Warhol Museum. It's a very interesting film because Andy chose Rene to play him, opposite Edie Sedgwick. I don't know how that happened, but Susan [Bottomly] was impersonating Andy's mother. I vaguely remember the movie. It was kind of interesting considering Andy's dynamic relationship with Rene.

Andy Warhol photobooth assemblage with Gerard Malanga for Gerard's Photobooth series, 1964. Photo © Gerard Malanga.

Manon: How did your relationship with Rene evolve later on?

Gerard: Well, the relationship between me and Rene got better as time went on. He started writing poems, which were quite mind-blowing, and I was getting him published in magazines. In fact, this morning I came across a magazine… let me see if I can get my hands on it. This is actually the first Rene Ricard ever published, in a magazine called Harbinger that was published in Austin, Texas. I'm on the cover with Andy, and Rene has two or three poems in the issue. I also have two or three poems published in it. There was a special supplement on the filmmaker Bruce Baillie. The editor and publisher was a friend of mine, Gregg Barrios. It stopped after this one issue, so this is a very rare magazine, and Rene's first appearance in print.

Manon: You mentioned that you lived with him at some point. How was his daily life?

Gerard: (laughs) Well, Rene’s daily life began probably at 11:00 in the morning when he would wake up. His bed was my couch in the living room. he slept on this couch for a whole year. He would organize his plans for the day, whether it was lunch somewhere with somebody or visiting an artist in his or her studio or an art gallery opening, dinner party, things like that. In fact, a lot of the time it included me also. Rene had a very lively existence.

Manon: Do you remember his drawings? Even as a young man, he was already doing those very beautiful hand drawings.

Gerard: Oh, the hand drawings. He didn't continue doing the hand drawings too much. But when he did, he was really good at it, almost like a kind of Leonardo da Vinci type drawing, something out of the Renaissance. He was just very talented at what he was doing, but he didn't take it seriously.

Manon: Can you tell the story of the time you sent Rene to replace you at an event of some sort, a screening? I love that story.

Gerard: Yes, this was during the time that I was performing with the Velvet Underground and I was invited to Cornell University in Ithaca, New York, to show movies and give a poetry reading. Andy was getting a little upset, he didn't want me to leave that night. I think he was getting maybe a little spiteful. It was very sensitive situation. I couldn't go to Ithaca, but I was committed to going there. So I had Rene take my place. I told him “Just pretend to be me.” He pretended to be me, but he was also being himself at the reading. All the students loved him and he had a great time. He came back with lots of money for the two of us, which we lived on for a month, going to Max’s Kansas City, having lunches and dinners and all that.

Manon: In 1968, you shot a film where he appears, Preraphaelite Dream, with Loulou de la Falaise.

Gerard: Well, whenever I was with a beautiful woman, Rene would show up, all of a sudden, out of nowhere (laughs). So, one day, I was doing some movies with Loulou de la Falaise and I threw Rene into a scene with her, which I filmed in the East Village. It worked out well. The film needs to be restored. I have to do that at some point.

Manon: What was the scene?

Gerard: Well, there was a scene where they're walking down the street on Second Avenue, towards St. Mark's Church, and they come into the garden. And then there's a scene where they're kind of swinging on a swing attached to a tree. It was very funny. I thought the branch would break, but no.

Rene Ricard and Loulou de la Falaise, 1968. Photo © Gerard Malanga.

Manon: You also appear together in a film by Warren Sonbert, Hall of Mirrors (1966).

Gerard: Warren was a cinematographer in one of my movies, In Search of the Miraculous (1967). He also appears in the movie. And Warren and I were very good friends. Rene was a good friend of Warren also. Warren was in the NYU film program at the time. He was a student. Very talented young man and very helpful with the movie.

Manon: And you were the one who shot Warhol’s screen test of Rene. Do you remember that moment?

Gerard: (laughs) Well, that moment is sort of like every other moment that happens when you shoot a screen test of somebody. It's a silent movie. No one is talking. There's no sound. And Rene was very placid, very peaceful, looking into the camera. That lasted three minutes and that was the end of it.

Manon: You took many pictures of him throughout your friendship.

Gerard: I did. I photographed Rene a lot, I believe, in spring of 1970, in Boston of all places. He was very campy, very dramatic. He was sitting on an old mattress in an alleyway. Very seedy situation. And that was really the first picture I took of him. And from that point on, whenever we were together, I would be there with the camera to take pictures. There were periods when I didn't see Rene. Like there was a period from, I want to say, 1971 until 1977. Then we reunited in ’77, and I took lots and lots of pictures of him then. Wherever we went, I had the camera with me. He enjoyed being photographed, and that was a lot of fun for me also. And I thought it was important to document Rene. There’s two or three pictures I took of him that were very kind of… moody type pictures where he was not looking at the camera. I like those a lot.

Manon: You mentioned that he was not always accepted in the poetic milieu at the time. Could you describe the poetic milieu at the time, and his place in it?

Gerard: I don't think I was accepted in the poetry milieu either. But it was fun encouraging Rene to be more present with himself. Some people liked him and some people didn't like him. He could turn a lot of people off sometimes. That happened, but certain poets got used to him, so it was good for a while.

Raymond Foye: Gerard, maybe you could talk a little bit about the literary milieu in Boston that Rene was a part of?

Gerard: The Cambridge milieu was something that I was sort of on the periphery of, but there were times when I would see Rene not in New York City, but in Cambridge or Boston. And one of those incidents was summer 1966. I went to Cambridge just as a holiday, but I brought a movie camera with me. Rene was hanging out with Susan Bottomly, who was a debutante, a real debutante. She was 17 at the time, graduated from high school. She looked a lot like Elizabeth Taylor, and Elizabeth Taylor was in a movie called National Velvet. So I came up with this name for her, International Velvet. We made a movie in a friend's house in Milton, Massachusetts, where Susan was putting on makeup for over thirty minutes. I was shooting with a Bolex so I had to change the reel every three minutes,. And the last reel, which was very playful, was Rene and Susan and a friend of theirs, Chase Mellon, who was a Harvard undergraduate at the time. We’re in the last scene together and Susan was wearing a bikini bathing suit. And Rene, very cleverly, without Susan paying any attention, pulled the bra of the bathing suit off. Susan, at that point, she was very inebriated. She was laughing at the whole thing.

Manon: Do you still have this film?

Gerard: Yes, I do. It’s black and white. It’s silent. It’s about 36 minutes. And it was Susan’s first movie ever. She went on to make a few movies with Andy, then she went off to Paris and ended up meeting someone and living there for a while.

Rene Ricard, London, 1972. Photo © Gerard Malanga.

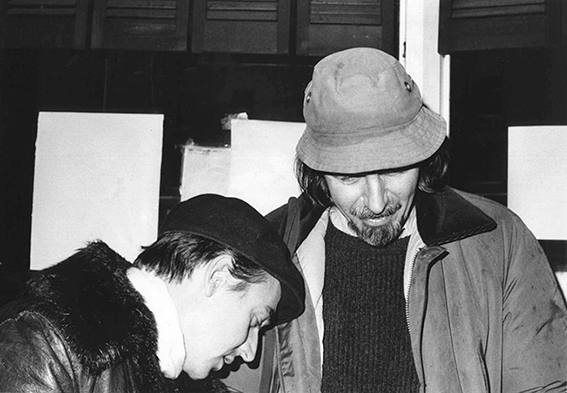

Raymond: Who were some of the poets that Rene modeled himself after? Who were the people he looked up to? Who were the ones that admired him?

Gerard: Interesting question. I think Larry Fagan was one person who was not enamored by Rene. Bill Berkson might have been suspicious of Rene at the beginning. Anne liked Rene a lot—Anne Waldman.

Raymond: He looked up to Robert Creeley, to John Wieners.

Gerard: Yes, of course. Robert Creeley adored Rene. They got along terrifically together. I think Creeley was quite surprised at the amount of talent that Rene had, in the poems he was writing. Quite amazing. It takes a lot for Bob to write a very long poem to somebody, and Bob wrote this exquisite poem, as you perhaps recall, to Rene. It's called “For Rene Ricard.”

Rene Ricard and Robert Creeley, 1976. Photo © Gerard Malanga.

Raymond: What about his wardrobe, his clothes? What can you say about how he dressed?

Gerard: That's a very interesting question, actually. Rene had a flair for, like, putting flowers around and tying flowers to his clothing, or having colored wristbands and stuff like that. All these kind of things that you wouldn't expect a guy to be doing. In that regard, it was very kind of fashionable. When I was filming him with Loulou de la Falaise, they had matching wristbands and it was very flaring.

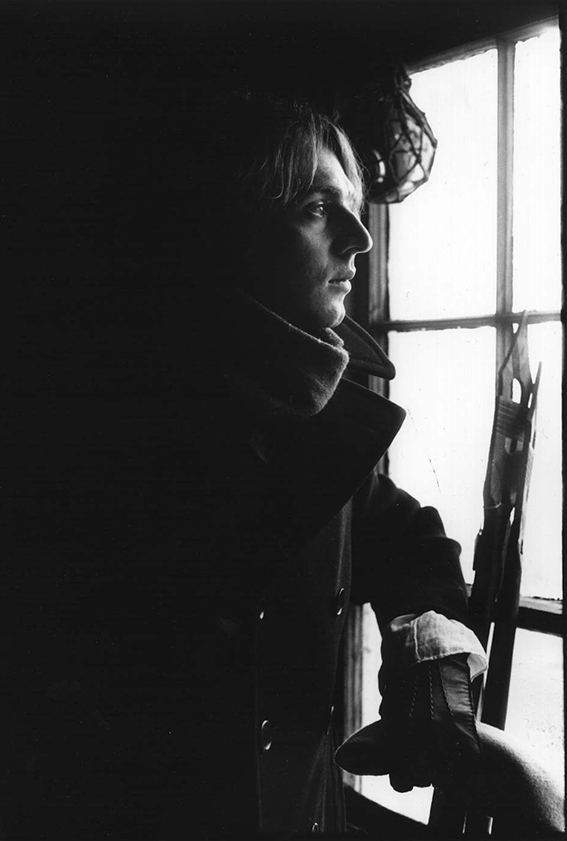

Manon: Could we speak about how, in 1978, you had the opportunity to be the editor of what was supposed to be a series of poetry books for the Dia Art Foundation, that ended up being just one single book—Rene Ricard 1979-1980, Rene Ricard’s first poetry book, published by Dia. Can you tell us about the context and how it went?

Gerard: In 1978, Rene was living with me in New York and Heiner Friedrich, who was the director of the Dia Art Foundation, was very enamored of Rene. Although I'm not sure if he was that familiar with Rene's poetry, but he sensed that there was something there. So he put me in charge, because Rene didn't seem to be very responsible about his own work, which is true. So I basically had to guide him, in terms of being more organized with his work. I was helping him do that. At the same time, we were putting a manuscript together and finally got something that seemed workable in that situation. And that was his first book of poetry. He had the idea for the Tiffany cover with the color, the exact color of the Tiffany catalogue. I hired the typesetter for the book, who was a letterpress publisher himself, Bruce Chandler of the Heron Press. Bruce still lives in Springfield, Massachusetts. It was very rare to do a book of 1,000 copies in letterpress. It was quite extraordinary to do that. Usually you can do a letterpress book of 300, 400 copies, but 1,000 copies, of course, there's a lot of wear and tear with the lead and the characters. So all of that book was printed with letterpress, it wasn't offset. And it had a very elegant sheen to it, in a way. But anyway, it was very successful. Heiner was very happy with the book. I created a contract for Rene that amounted to a $5,000 advance for the book, which was really unheard of in the poetry world. And then Heiner came up with the idea of having Rene publicize the book with five different poetry readings that would be sponsored by Dia. And Rene would get paid $1,000 per reading. But the poetry reading part never got off the ground, it became a very complicated situation because of Rene’s behavior.

Robert Mapplethorpe and Rene Ricard, 1977. Photo © Gerard Malanga.

Manon: Do you remember the process of selecting and editing the poems?

Gerard: I do to some extent. It's been a while. But in terms of editing the book with Rene, we were able to come upon a way of giving the table of contents a certain kind of structure that would work, you know. It was a full-length book of poetry and it was all of Rene's work from, I don’t know, the previous three years.

Manon: You told me once that this close relationship with him broke at some point. Will you tell us how it happened?

Gerard: Well, it's a very sad story. It really hasn't been discussed before. At some point, Rene was going to give a reading in Staten Island, which is pretty far away from Manhattan, with another poet named Alice Notley, who happens to live in Paris now. So Rene called up the Dia office to say, “I'm going to collect my first $1,000 check.” And Heiner got very upset about this, because this was not a reading that Dia organized. It was something that was organized by Rene or by Alice. So I was at the office one day and one of the managers came to me and said, “We have a problem, Rene called up to say he was going to come and pick up a check for $1,000 for a reading we have nothing to do with. Can you talk to him about this?” So I said I would do that next time I see him, which was a few days later at an art gallery opening. And I took Rene aside and said, “I have some news to tell you.” And I started to explain to him the situation with Dia, that they weren't going to pay him $1,000 for the reading. Before I could finish, he was attacking me. He turned on his heels and just walked away with his chin up in the air and that was the end of it. So Heiner stopped the whole project of future books.

Manon: It never got better between the two of you?

Gerard: Not at all. Rene, as I discovered, held grudges. You know what that means? A grudge is when you're feeling that you want to attack your enemy. So that was Rene's position on that. There's an old expression, which is very funny, I find. “Kill the messenger.” And I was the messenger.

Manon: Do you remember the last time you saw him and how you felt about that?

Gerard: We did do a book party for the book. This was after the argument. At a bookstore. And it was after that book party that I stopped seeing Rene. After that event—ironically, because we circulated with the same people a lot of the time—I never had the occasion to run into him again.

Manon: Well, thank you so much.

Gerard: Thank you.

Manon: Your cat remained very quiet.

Gerard: Yeah, the cat is a sleeper. [To the cat:] Hi, honey.

Raymond: Gerard, I see you have a folder here. It says “Rene Ricard prints.” Can we open this?

Gerard: No.

(Everyone laughs)

Rene Ricard, New Bedford, 1970. Photo © Gerard Malanga.

-

Born in the Bronx in 1943, Gerard Malanga is an American poet, photographer, filmmaker, and archivist, and a pivotal figure of the New York art scene. He was Andy Warhol’s assistant and collaborator at The Factory from 1963 to 1970, where he filmed over 500 "Screen Tests." In 1969, he founded Interview magazine with John Wilcock & Andy Warhol. From 1970, he dedicated himself to his own photography practice, with a special attention to the portrayal of artists and poets, but also nudes and urban documentation. He has directed several movies, including In Search of the Miraculous (1967), Preraphaelite Dream (1968), and Gerard Malanga’s Film Notebooks (2005), which had its world premiere at the Vienna International Film Festival, also known as the Viennale. He is the author of several poetry books, including No Respect: New & Selected Poems 1964-2000 (Black Sparrow Press, 2001) and The New Mélancholia & Other Poems (Bottle of Smoke Press, 2021). His most recent book is Gerard Malanga’s Secret Cinema (2023), from Waverly Press. His poetry has been published in Poetry, Paris Review, Yale Review and The New Yorker, among others. He lives in the Hudson Valley region with his cat, Odie.

Rene Ricard was an American poet, artist and actor. He was born in 1946 and grew up in New Bedford, Massachusetts. After a troubled childhood, he fled to Boston as a teenager where he came into contact with literary and artistic circles. At the age of eighteen, he moved to New York City and became a central figure in the city’s art and literary scene. Ricard appeared in several films by Andy Warhol and continued to act in many independent films throughout his life. In the 1980s, he wrote two major collections of poetry, as well as important essays and articles, some of which were instrumental in launching the careers of artists such as Julian Schnabel and Jean-Michel Basquiat (he wrote the famous article “The Radiant Child” in Artforum in 1981). Beginning in the 1990s, he developed a pictorial body of work and exhibited his paintings in various galleries in the U.K. and the U.S. He died in New York in 2014.

-

Copy-edited by Madeleine Compagnon and Raymond Foye.